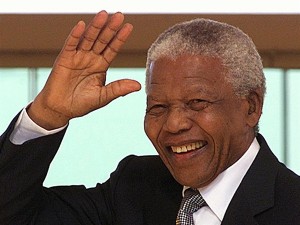

Ekiti State Governor Kayode Fayemi spoke this morning on the passage of the icon Nelson Mandela.

He said: “The passing of Nelson Mandela after his prolonged hospitalisation should not be a cause for sadness on any account. We extend our deepest sympathies to his family and offer our prayers to them and the people of South Africa. But we also recognise that his passing at the ripe old age of 95 is a fitting crown to the rich full life that Madiba lived, playing a starring role in what is surely the 20th century’s most compelling odyssey of human freedom from tyranny.

“Rather than mourning, Mandela’s transition into glory should be an occasion for celebration and reflection. Firstly, we celebrate the final consummation of a life well spent. The phrase “a life well spent” which is commonly used in obituaries has become an overworked cliché but in the case of Madiba it is not a cliché at all. It is more than worthily applied to describe a man who expended his energies in the service of humanity, risking everything including his life to actualize the ideal of freedom. It is this exemplary life that we have much cause to celebrate.

Even, as we revel in the honour and blessing of having lived to witness the life and times of one of history’s most iconic political figures, we must also ponder his luminous legacy. His death closes an epic story of the triumph of the human spirit over injustice and tyranny.

“Born into a country characterised by apartheid and racial hate, where the black majority was ruled by a white supremacist minority, Mandela discovered his cause and his life’s mission early enough. As the liberation movement’s most prominent militant leader, Mandela had been effective as a shadowy and elusive figure orchestrating sabotage attacks on government facilities and showcasing the ability of a long-oppressed people to fight for their freedom.

“But as a prisoner, he became the symbol of apartheid’s oppressive inhumanity. It was Mandela’s face that readily came to mind when people the world over thought and talked about South Africa. His imprisonment helped to mobilise global public opinion and a campaign for international sanctions against South Africa, as well as near universal censure and isolation of the apartheid regime. It was this suffocating and strangulating isolation of South Africa as a pariah state and mounting unrest on the streets that finally compelled reformist elements within the establishment to renegotiate South Africa’s destiny. When Mandela was finally released from prison in 1990, after nearly three decades in the custody of the apartheid state, he emerged as a figure of unparalleled moral authority.

“Mandela successfully negotiated constitutional black majority rule – achieving one of the core aims of the ANC. In so doing, he had to navigate a turbulent period of transition during which chronic violence between Xhosas and Zulus, and between white right wing extremists and black zealots threatened to degenerate into civil war. Remarkably, Mandela emerged from prison preaching forgiveness and reconciliation as the only path to a new and sustainable South Africa. He understood that even as white domination had proven repressive and unjust, so too would black domination prove to be unsustainable. He insisted on the democratic and multi-racial vision enshrined in the freedom charter, the guiding document of the liberation movement.

“He wisely charted a course between the two extremes of black anger and lust for vengeance on one hand as well as white fear and resistance to change on the other. The challenge of doing so was immense because white extremists and black extremists were threatening to unleash death and destruction. Many watchers felt that a racial civil war between whites and blacks and even war between ANC cadres and the Zulu Inkatha Freedom Party were inevitable. Mandela’s conciliatory posture helped to defuse those tensions and shepherd the nation through a transition process that culminated in his election as the first democratically elected president of the country. This is how South Africa was transformed from an apartheid state to a multi-racial democracy – the rainbow country.

“It must be said that the work of liberating South Africa was not Mandela’s alone and he has never claimed any such messianic mantle for himself. His iconic status as a pivotal figure in the odyssey of South African liberation is un-impeachable. But he belonged to a very distinguished cast of leaders that included freedom fighters like Oliver Tambo, Walter Sisulu and Govan Mbeki. And these heroic freedom fighters were themselves the second generation of the struggle ordained by the founders of the African National Congress. They were heirs to Albert Luthuli, John Dube, Sol Plaatje and other heroic patriots. Together these patriots forged a political tradition of such resilience that it altered the course of South Africa’s history.

“This is an important point because the idea of Mandela can be easily reduced to championing the emergence of rare superhuman political saints. This is not the leadership lesson that we should be taking away from Mandela’s odyssey. Mandela was the product of an already established revolutionary tradition. Side by side with his cohorts, great liberation fighters like Tambo and Sisulu, he was comfortable. There was a remarkable absence of personality clashes; egos were submerged in the cause of the greater good of securing a free South Africa. There was little or none of the jostling for leadership that often characterizes liberation movements on the cusp of attaining power.

“This is something we must ponder as we reflect upon the state of leadership in our country. Our challenge is not to produce one messianic leader but to create a tradition of patriotic leadership and raise a corps of leaders bound by a common ethos as was the case with South Africa. As James Freeman Clark said, “A politician thinks of the next election, a statesman, of the next generation.” Leadership is a continuum and for our leadership to truly stand the test of time it must be driven by a trans-generational perspective. We must build up those who will take our exertions for a better society to higher levels. I am convinced that through carefully and consciously developed formal and informal programmes of leadership development, we can build a cadre of young Nigerians who are committed to social transformation and genuinely want to work for change. “This entails a shift away from the idea of the “leader as messiah” – the notion that all it takes to transform our society is the miraculous emergence of one extraordinarily endowed leader. We simply cannot afford to reduce leadership to political Messianism. Mandela, despite his own leadership gifts and his track record, did not think of himself as being indispensable. He relinquished presidential power willingly and gracefully and ceded the limelight to the younger Thabo Mbeki. And when he left office, he wisely refrained from being an overbearing post-presidential presence and let his younger successor fully take up the reins of leadership. In so doing, he was setting an example – that the older generation must give way to the younger and allow their nations move forward.

“Mandela’s willingness to leave power stands in stark contrast to a number of situations in Africa where erstwhile liberation fighters having assumed power have simply found it impossible to relinquish the presidency. Many have become sit-tight despots. Mo Ibrahim set up his annual leadership prize partly to motivate African leaders to give up power and leave the stage willingly. There have been years when no leader was nominated because they track record in office simply did not match the criteria for nomination. This is a pungent commentary on the state of leadership on the continent. Mandela stands as a shimmering example of what real leadership looks like.

“Tributes often read like hagiographies. To be sure, Mandela was not perfect. He made mistakes. Many South Africans feel that the ANC while earning black majority rule did not pay sufficient attention to addressing racially-based economic equality. As a result some of the development indices in the country are actually worse now than they were before Mandela became president. There is much work to be done in the areas of housing, education and employment.

“However, the pursuit of freedom is not accomplished in one generation. Mandela and his generation fought for political liberation. Another generation must now rise up and take up the bottom and begin the battle against inequality and poverty. Fortunately, in Mandela they have the most illustrious of examples to draw from and emulate.”

Adieu, Madiba.

This article was first published in ThisDay

Last modified: December 6, 2013