Let me begin with Chinweizu, the non-conformist pan- African intellectual who wrote The West and the Rest of Us, a lucid, penetrating and fierce critique of the imperial conquest and enslavement of Africa. In October 1990, Chinweizu published Anatomy of Female Power,a book he described as amasculinist dissection of matriarchy. Echoing Esther Vilar’s The Manipulated Man, he argues with passion and wit in this book that men may rule the world, but women rule the men who rule the world. According to him: ‘’There are five conditions which enable women to get what they want from men: women’s control of the womb; women’s control of the kitchen; women’s control of the cradle; the psychological immaturity of men relative to women; and man’s tendency to be deranged by his own excited penis.” Chinweizu, not surprisingly, dedicates Anatomy of Female Powerto the countless number of women who have slipped in and out of his life especially those who attempted to marry him! He calls on men of the world to unite and refuse to accept the claim that men are natural oppressors of women. Chinweizu’sbook, I must admit, is seductive. But the moment you ask yourself the question: Is there really no oppression to liberate women from? And if your answer is a resounding yes, his argument then becomes not just provocative but reductionist.

Let me begin with Chinweizu, the non-conformist pan- African intellectual who wrote The West and the Rest of Us, a lucid, penetrating and fierce critique of the imperial conquest and enslavement of Africa. In October 1990, Chinweizu published Anatomy of Female Power,a book he described as amasculinist dissection of matriarchy. Echoing Esther Vilar’s The Manipulated Man, he argues with passion and wit in this book that men may rule the world, but women rule the men who rule the world. According to him: ‘’There are five conditions which enable women to get what they want from men: women’s control of the womb; women’s control of the kitchen; women’s control of the cradle; the psychological immaturity of men relative to women; and man’s tendency to be deranged by his own excited penis.” Chinweizu, not surprisingly, dedicates Anatomy of Female Powerto the countless number of women who have slipped in and out of his life especially those who attempted to marry him! He calls on men of the world to unite and refuse to accept the claim that men are natural oppressors of women. Chinweizu’sbook, I must admit, is seductive. But the moment you ask yourself the question: Is there really no oppression to liberate women from? And if your answer is a resounding yes, his argument then becomes not just provocative but reductionist.

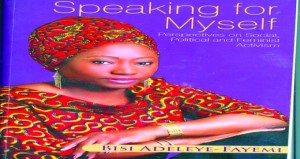

In Speaking for Myself BisiAdeleye-Fayemi indicts such reductionist patriarchal notions and ideas.The five hundred-page-book is a generous collection of many essays, academic papers, lectures, speeches, opinion pieces in newspapers and magazines, poems, reviews and tributes that she wrote between 1987 and 2012. All the pieces tell a coherent story of three decades of dedication to the cause of women, a mission in which she has found true meaning and contentment. We have here extended ruminations of a giver of light. With depth and clarity of thought she combines personal anecdotes and layers of data to offer a lively and rigorous defence of the concerns and needs of women, particularly women in Africa. Substantially, her contention is that a society where liberty, equality and fraternity do not have a prime of place is very dangerous to live in.We are told that, apart from the love and encouragement of his father in her early years, the University of Ife was where the seeds of her intellectual engagements with feminism were planted and nurtured. This is where she earned her first and second degrees in History and International Relations. This was where she read Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch for the first time. Greer’s book was given to her by Dr. Femi Taiwo, now a professor at Cornell University in America. The Female Eunuch was a source of inspiration. As she grew rapidly in thought she wrote a joint paper with Dr. Taiwo for a conference organised by Professor Bolanle Awe’s Women’s Research and Documentation Centre at the University of Ibadan in 1987. That paper remains relevant to women’s studies. The mentor and the mentee argue in the paper that: “There is no future for women’s studies in Nigeria unless it is premised on some plausible, coherent, and adequate theory (or theories) of women’s oppression which, while remaining faithful to the universalist dimensions of theory construction, will be alert to the specificity of the Nigerian situation and its diverse manifestations and reorient itself accordingly.” They propose that women studies be taught in our Universities. More crucially, they observe that “we should not permit ourselves to think that the emancipation of women can be done outside the context of the general emancipation of humankind’’.

Ten years of working at Akina Mama wa Afrika (AMwA) further strengthened her theoretical capacity and resolve. That she designed the African Women’s Leadership Institute (AWLI), a training centre for young African women; that she helped to establish the African Feminist Forum which serves as a rallying point for African feminist scholars; that she, along with activists like Sarah Mukasa, built and nurtured the African Women’s Development Fund (AWDF); that the Ekiti Development Foundation came into being and, in a short time, inspired a legislation against rape, are all a result ofreflections and game –changing experiences.

As an African feminist she bounces herself in this book against all Eurocentric white feminists and the local conservative women organisations peopled by those she describes as home fronters and gender activists as opposed to feminist activists. It is a clear ideological position she is not afraid to take. She argues robustly that all identities that locate women in spaces that make them vulnerable are not acceptable. She questions histories and heroics which refuse to honour women who excelled or who were just difficult to understand or categorise. In essay after essay, she calls for a dismantling of regional and global structures of social injustices which reduce women to second class citizens, which make their labour unremunerated and which make them permanent objects of validation by men. The increased impoverishment of the African continent, Adeleye-Fayemi argues, inevitably brings about the disempowerment of women, or to use her much beloved phrase, brings about “the feminisation of poverty”. She proves convincingly that, due to biological, social and economic reasons, women in Africa suffer more from the consequences of inadequate healthcare, conflicts and wars. How come, she asks, that women do not have the right to transfer citizenship to another national? “If you are a full citizen of a country, you should have the power to legally transfer citizenship. If the constitution says that you cannot, then your status as a full citizen is questionable”.

To claim and sustain political space for women is essential. But access to mainstream decision-making and political power for African women is very difficult. If political terrain is tough for men, it is tougher for women. She observes that “The outrageous costs of running for office, the logistics of coordinating an effective campaign, the fluidity of politicians’ meeting hours, fear of violence, the need for a political godfather – these are factors that serve to exclude women from making a decision to serve their countries”. Even when women survive all these hurdles, what about the difficulty of working in an environment that is so hostile to the empowerment and equality of women? To her, this should not lead to indifference. The situation demands courage, it demands that serious women should be identified, put forward and supported. This will involve cultivating leadership among young women.She encourages feminist activists to work with men and seek them out as allies. But she quickly enters a caveat: carrying men along must not include employing them to run women’s organisations, speaking on behalf of women, counselling women who are suffering from abuse. She suspects that men will not give up easily the powers and privileges which patriarchy confers on them. In an attempt to solve the problem of women subjugation, however, feminist activists should not end up instigating their sons to form a men’s movement for equality.

The negative representations of women in literature, drama, films, music, advert copies and other forms of communication have always given BisiAdeleye-Fayemi a lot of concern. In this book, she interrogates the forms and contents of Shina Peters’ ‘Shinamania’, Jimoh Aliu’s Arelu, Isola Ogunsola Iyawo Alalubosa and shows how women are trivialised or dubiously elevated when they should just be celebrated or condemned as human beings if they truly deserve it. She praises ‘Warrior Marks’, Alice Walker’s documentary on genital mutilation, not only for the veracity of her story line and the power of photography but also because the documentary could serve as an effective weapon for all those who value human dignity. You will recall that the African Women Development Fund sponsored a well-attended conference in Lagos three years ago toexamine the dynamics of women’s representations in Nollywood films. Professor Abena Busia, Dr. Bunmi Oyinsan and Joke Silva were among the resource persons. She suggests that one way of projecting the positive image of African women, of putting an end to what she calls ‘’the effective silencing of African Women’s voices and experiences” is for all gifted feminist activists to rise to the challenge of writing their own stories. According to her, “We have to scale up our contributions to the rich debates on feminist theory and practice worldwide”. For her, it is only when all voices have been heard can feminismbe described as truly global.

If all the articles she wrote occasionally for newspapers, radio, magazines, journals and television are in this book it is essentially to demonstrate that she has always added her own voice to those of others who fight for comfortable space for women through their writings. As you read them, and possibly disagree with some of her positions, you will not miss the tender honesty of her writings, their unfailing sense of justice andthe weight of their wisdom.She makes a strong case for courage, solidarity and accountability. She also talks about the necessity of memory in our national lives. Her argument is that if we don’t forget the bad ones among us, we are most likely not going to forget the good ones. She remembers the living and the dead from whom she has learnt a lot. She salutes Mrs Ronke Okusanya and other great women in Ekiti for the dignity in their exemplary lives. She appreciates the likes of Bene Madunagu, Tawakkul Karman, Ellen Johnson-SirLeaf, Laymah Gbowee, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Aisa Imam, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala and Joyce Banda. By paying glowing tributes to her father, Mr Emmanuel Adeleye, who just left his house one day and has not been found, dead or alive, since then; by paying tribute to Dr.Tajudeen Abdul Raheem, Funmi Olayinka, mama Dorcas Fayemi, Flora Nwapa, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, Sally Mugabe, Wangari Maathai, Kudirat Abiola, May Ellen Ezikiel, Brenda Fassie, Yetunde Obafemi, Annie Mubanga and a host of others who have spent their lives keeping faith with women, caring for the underdogs, working for the common good, raising wonderful families and building institutions, she calls our attention to some of the virtues that will make our country and the world grow and endure.

This article was first published in The Nation

Last modified: December 12, 2013